(vibrant electronic music) - So, jumpsuits.

All fun and games until you wanna go to the bathroom. (group laughing) And, literally, that's why I did that, so I could do that joke.

Thank you so much for having me here, everybody. At least, you know, it's amusing so far.

What I wanted to talk about today is something that's really super close to my heart, which is around design ethics, it's around trust. It's around how we as designers use the incredible power and opportunity that we have to make sure that what gets put out there in the world is for societal benefit rather than societal detriment. I've been in the industry, jeepers, more than two decades now, which is slightly terrifying. I was at an industry panel this morning for the university of Sydney sitting in front of a whole bunch of very bright-eyed young design students telling them what the real world was like.

And, told them the story of how I got started, which was writing for a magazine called: Internet.au and the Australian Knit Directory in 1995 where I'd review websites.

And we'd print it out on the paper and, then, fasten it with staples and sell it in news agencies like it was a thing that was worthy of dollars. And I could see in their eyes the shock that someone at some point in time in the past thought they could put what was on the internet in a magazine.

So, I have been doing this for a very long time. And where we are right now in our industry, in the world, in our political systems we are in a trust crisis.

So, I am seeing many, many examples of people getting things badly wrong, very badly wrong. When we're talking about trust what we're talking about is we're being willing to allow others, we're being vulnerable allowing others to have power over us because we believe that they will do something that is for our benefit, they won't take advantage of us, they won't use us for their purposes.

That's why we trust.

And what we're seeing at the moment in industry, in politics is we are seeing our trust being broken.

We are seeing our vulnerability being abused, used and abused by organisations.

And I think as designers I am not hearing enough of us having the conversation in our projects saying: Just because we can do this, should we? Has anybody had a stand up, fall down, smack down fight in their organisation about whether or not something is ethical and right. How'd you go, did you win? Oh.

Did anybody win? Did anybody get a half of a win? At least you asked the question.

Most of the designers that I'm seeing out in industry either aren't asking the questions or don't even know that there are questions to be asked or a conversation to be had.

I probably don't need to explain to you how these fit into trust crisis.

But these are three of the logos who have breached and, abused the trust that we vulnerably gave to them. So, I mean, Facebook they gave their data from 87 million of their users to a political organisation, a political social organisation, Cambridge Analytica you've probably seen this.

Has anybody watched the Netflix documentary on this? Yeah, really good stuff, do have a look at it. But basically they gave it to them so that they could swing an election.

Now, that sounds terrible.

But do you know what? It's working exactly as it was designed to work. It was designed to be able to do that.

And there are a bunch of designers who did not have a conversation to say: Hey, is this the right thing to do? It got even worse than that.

They were, they admitted and this is just last year they admitted that hackers had gained access to over 50 million of their users login information. But they had, this information has to be dragged out of them. They don't volunteer it. And, then, finally their year last year closed that they had given Netflix, Spotify, Microsoft, Yahoo! and, Amazon access to its users personal data.

And, in some cases their private messages.

Now, this is a huge breach of trust.

But all of it is working exactly as it has been designed to do.

And do you know what? The lie you tell every time you get on the internet, I have read and agree to the terms and conditions. That allowed them to do that.

But there was a designer who was involved in that that went: I'm gonna back it, I'm gonna back this play. Volkswagen is still tryin' to come back from its emissions defeat device.

People know about that one.

They manufactured a device so that they could show that their carbon emissions were way lower than they actually were.

Huge breach of trust because they were selling everybody this idea of great, efficient automotive engineering that was going to be great for the planet.

Actually, not.

And Boeing, incredibly, with it's 737 MAX jets it had two planes go down.

It had been stopped from flying in about 42 countries. But it actually took a presidential order to pull them out of the air full stop.

And, then, they admitted that they'd known about the problem since 2017. And had done nothing about it because they didn't wanna retrain pilots.

And they allowed it to go through.

So, what I see is that we are designers who have a responsibility to get in the way of some of these behaviours. And then there's this guy.

Donald Trump bashing is too easy.

So, I'm not gonna do that.

But fake news had been around since the invention of news. We have always had fake news.

There's always been misinformation, propaganda, satire. You know, some people think The Betoota Advocate is a real thing.

I think Channel 9 News quoted them one day. It was hilarious.

But this has all been around.

And the fake news while it's been around in history now what we have is a situation where robots, AIs, machine learning are creating fake news on these social platforms because they're designed to work that way.

And they are pumping it out at a rate that is way faster than it ever was in history. And it's actually they're getting so good at it that the prediction is that it's gonna take an AI to be able to detect an AI.

As if, if they're pumping out the information, misinformation.

And because it's popular doesn't necessarily mean it's true. We see a lot of misinformation on social media and it relies on likes and sharing and things like that. And as soon as you get in.

Well, who has actually on their social media started to follow someone or become friends with someone from a different friendship group and then you get on their Facebook and you find out that your viewpoint is completely the antithesis of theirs? I have a relative (laughs) who, you know, I friended on Facebook because it was my relative.

And then discovered her incredible nationalistic sentiment along the lines of, you know, go back on your boats to where you came from. She's a migrant who came over on a boat in the 1950s. So, I think we have a lot, like, social media has a lot to answer for. And it is actually, this, I think there's something that you should go and have a look at it from a design perspective. It's called: The Spinner.

So, this is an example of where designers really should have gotten involved and asked the questions. So, the spinner allows you to pay $49 to present content to people who you select on the internet or on your social media to subliminally message to them your viewpoint or what you want from them.

And the packages are presented such as: Get your wife to initiate sex more often.

Here's all the content marketing that we'll put in front of her so that that happens. Another one slightly less bad.

Get a dog for your family.

Who would I target? My mom and dad.

There's also, lose weight, yes.

Reasons to lose weight.

10 reasons why you should really lose weight. 49 bucks will put this sort of content in front of your loved ones or people who you want to target.

I think another package is, get back together with your ex. So, you can target your ex.

This, I shit you not, this is a real service. $49 will buy you this.

And in the discussion about it some of the designers who were talking about their thoughts on it, one guy and I think this is the best description, he called it: Gaslighting as a service.

Where was the conversation about breaching trust? So, the people who are on these platforms they're trusting that somebody else isn't gonna be able to pay 49 bucks to gaslight them. You know? These are conversations that we need to be having. These are conversations that I hope that you're thinking: Hey, maybe there's a few more conversations I could be having in my workplace, in my projects in order to make sure that I'm not going to be party to something like The Spinner.

Because anything that we design is going to face questions of trustworthiness, anything because we are super suspicious these days. And that is appropriate.

But trust is becoming so much more important due to the breaches that we see.

And we in our projects, in our work with our clients, with our own companies, we're going to have to succeed. We're gonna need trust as a fundamental mechanism, as part of what we provide as outcomes for the people we design for.

And more and more of what we design is going to be invisible.

So, think about all of the invisible decisions that get made for you already, what you get recommended on Netflix, what Amazon thinks you might like to buy.

All of these decisions are based on data and invisible information about you.

And the way that they're making those decisions are invisible.

Who's making the decisions about how those algorithms work? Developers.

Now, I'm not dissing developers.

But their job and training more often than not is creating great code.

Not necessarily asking the hard questions of the humans who are involved.

Should I create this code to do this thing? Is this the right thing for us to do? And I feel like I would like to give this talk, have we got developers in the room or are we all designers? Yeah, so, I'm really excited that you will be able to take away this.

And if you're not already asking these questions be asking these questions.

I know you're asking these questions, Ben.

I have faith in you.

So, how do we build trust into invisible products? Because we have a layer of technology that sits across and it's giving us experiences in seamless and frictionless ways.

And the reason why it's seamless and frictionless is because all of that invisible decision making is happening in the background.

Are we actually having the conversation about how these decisions are getting made? And what does the algorithm do? My thinking, I saw a suggestion that in terms of transparency for algorithms you have to, in your food ingredients you have to list what the ingredients are in the product that you put out.

Does it not follow that it's appropriate for us to list out how an algorithm gets to it's decision making? How does it get to the end recommendation? Shouldn't it explain itself and give us some level of comfort that it actually has been done in a ethical and in a considered way? And in a way that's not going to breach and abuse our trust? So we generate huge amounts of data.

We probably don't even know how much there is out there. Does anybody know what their data footprint is? I don't, I don't.

I have a vague idea of what Google picks up when you Google me but I don't know who knows what about me.

And I'm sure that Facebook follow me around like chewing gum on my shoe.

But we might engage with so many services that are automated.

And basically it's becoming harder and harder to grasp the effects of our actions.

It's very hard to know when you press the button that says: I read and agree to the terms and conditions, what did you actually agree to? Does that sound like consent to you if we know that nobody reads it? Do you think you've actually consented? So, I have, you know, I have questions for organisations that are going to continue to perpetuate this massive terms and conditions that nobody reads as to whether or not they have got consent. I don't think that they have.

I don't think you can call that consent.

'Cause the invisibility is increasing.

And more and more is happening behind the scenes. So, we got some mind blowing stats up there. From Forbes it's actually 2.5 quintillion, that's 18 zeros of data created every single day. I don't even know how big that is.

That is a monstrous statistic.

And we're looking at having 200 billion smart devices out in the world by 2020.

Guess what? That's in two months, two months.

200 billion smart devices out in the world. And also by 2020 and this one's from Juniper, 85% of customer interactions that a company has will be handled without human intervention. In two months, people, two months.

And that'll increase to 95% by 2025.

So, that's a lot of invisible decision making. And a lot of trust that we're putting into these organisations. Trust is actually decreasing in society.

The Edelman Trust Barometer talks about trust year on year how much we trust our institutions, how much we trust the government.

And we're looking at a decrease, an increase in general distrust in institutions. And the U.S. is suffering the most from that. They're looking at a 43% trust in its institutions now. And dropping.

And this is of their own making.

It's not entirely fair.

The construct of what's going on in the United States now is the contributing factor to this absolutely. But contributing to the fact that Donald Trump's in power and the way that he utilises media.

Social media is built and designed to deliver the messages that he's putting out there, to deliver anybody's messages that they're putting out there.

Have you been following Elizabeth Warren and the fake ads that she's putting up on Facebook? She says they're fake.

Facebook knows they're fake.

Facebook runs them anyway.

And it's really it's quite astonishing that our technology is enabling these absolute fabrications. Who do you trust anymore? There's some incredible work that we've managed to do in Designit with about half an hour of research and instruction in creating deep fakes.

And we created a deep fake of the Danish Prime Minister talking about something and agreeing to something that he never ever would.

Now, this individual who did this prototype work is not a technologist, he's not a developer. He just used some tools that you can get online now to create a deep fake, which is an image of a human who you have manipulated to say and deliver a message that you want them to. And they haven't done it.

They, I think deep faking also they did it in the Star Wars, recent Star Wars films with Carrie Fisher.

And trust is essential because all of the human relationships and the interactions that we have are based on trust. And if we don't have that trust, if we're not able to be vulnerable with these organisations and with this society, we can't function in society, we can't be a part of society.

And we're actually engineered to trust.

We are the only species that has the ability to trust another through our brain chemistry.

So, one of it is the theory of the mind.

So, the hypertrophy cortex allows us to actually put ourselves and transport ourselves into someone else's mind to go: Yeah, I know what they're thinking.

And that is something that allows us to trust. The other thing that allows us to trust is the fact that we have empathy.

And the research that's been done into that is that empathy creates oxytocin, which makes us, like, it gives us, sorts out our anxiety when we're with other people so we feel more relaxed. And oxytocin also generates dopamine, which is the, do more of this thing in our brain. And empathy allows us to really put ourselves into other people's shoes and to understand their emotions and therefore trust that they will do no harm to us. So, our brain chemistry actually provides the ability to trust.

So, trust can be designed for.

And I'm just gonna go through an exploration of what you'd need to be considering in these conversations when you're trying to design something to be trustworthy. You've got about three different ways that people can move forward.

So, you gotta get something done.

Do you trust it, do you not? So, the option number one is you move forward with risk. You know that you don't know all the things that you could know about this, you don't entirely trust it but you can't stop time. You have to move forward in whatever it is that you're doing therefore you accept the risk.

So, that is one way in which you can move forward. The second way in which you can move forward is with awareness.

So, you can be aware of the risks of whatever it is that you're trying to do. Of, you know, not reading the terms and conditions. But you will accept that and progress and continue with whatever it is that you're trying to do. But not in such a way that you feel like you've been forced to 'cause you don't have any options, which is the more risky path.

Or you can actually proceed with trust, which is where you can move forward with confidence because you actually know what's gonna happen. You're with someone you trust.

Or you've got a trust partner that's involved. And these are the kinds of relationships that we want to foster.

Risk and awareness, like, most products move forward in neither one of those two categories.

They move forward going: Here's the risk, take it or lave it.

Which is I guess a little bit the way that people approach Facebook.

Or, you know, awareness.

People will move forward but not with a sense of trust. And even when you're gonna be confident, so, in that, like, purple column.

Even though you're confident and you trust there's still al level of vulnerability that we expose ourselves to when we trust.

And it's an invaluable bond.

It is actually a social contract that you're making with a human or an institution.

And it lets us get things done.

If you do not trust something or somebody or an organisation you cannot progress, you can't move forward. So, unless you actually have this social contract of trust nothing will get done.

So, can you see why it's so important that we're talking about this and that we include this in our project discussions: How do we actually get people to trust what we're doing in order for us to get things done? Otherwise nothing happens.

I've talked about invisibility and how this is increasing. Our interfaces are disappearing.

More and more of our interfaces are disappearing. And even the things that give us a sense that we have an interface like our lovely telephones and, oh, I called it a telephone (laughs).

Our smart devices, they give us a sense that there's an interface there. But everything that it's doing and all the decisions that are being made are all happening in the back end.

I see Amy noddin' away there as a developer in the room. We've done a lot of investigation into this. So, at Designit we have a few experimentation spaces that we're playing with.

One of the experimentation spaces is this trusting invisibility.

We recognise that this is happening and we need to actually have a plan for designing for trust. We have two other experimentation spaces come talk to me about those later.

I wanna give you an example of how an organisation did do some design for trust.

So, this is Jaguar-Land Rover.

So, they're trying out driverless cars.

They're prototyping driverless cars.

Driverless cars have got a bit of a bad rep. Number one, because they decapitated a guy going under a truck by accident.

Number two, they're fed terrible training data which didn't include people in wheel chairs. So, given the option it ran over a person in a wheel chair rather than hitting something else that was less damaging. And so, there is actually a big divide between whether or not somebody's willing to trust a driverless car or not trust a driverless car.

And what they did was they actually created this prototype. And you see how he's got the little eyes on the front. So, what that does is if there's a pedestrian who's walking across the road, the eyes will see it, acknowledge it, follow it walking across the road so that they get a sense, the pedestrian has a sense of trust that they've been seen and they re not going to be run over.

So this is a, it's a simple and quite cute example of how you can design trust into an invisible interface. And these are the kinds of creative solutions that we're all gonna be needing to come up with. But they're not gonna come up unless we're asking the hard questions at the start of: Is this trustworthy? Why isn't it trustworthy? what is it that I can do with my design work to create that trust bond? And what does it actually mean in practise? So, we unpacked a lot of this to figure out: How has trust moved forward across society and history? As part of this explorations space.

So, if you have a look at the history of trust, we have had a society that lived in much smaller communities where we depended on one another, interpersonal relationships were essential to us actually getting anything done.

And it was also possible to know the majority of the group. So, that we were living in smaller communities and that we knew people.

We had a sense of who they were and what they did. It was a more manageable, I guess, size for trust. And that most prevalent trust type or trust form was called: Individual trust.

I trust you.

You trust me.

As individuals we trust each other.

We have that today but less so because we are a huge group of people in the world and we don't know everybody.

And as we've gone through time and community numbers increased what we ended up with is something that's called: Institutional trust or systematic trust beg your pardon. So, it's trusting in institutions.

So, as institutions started to facilitate activities such as banking, trading, things that required you to trust somebody that you didn't know you started putting your trust in the institution itself. And this is something that modern society this is basically what modern society is built on. We, ha-ha, trust our banks to do right by us (laughs). Royal Commission.

And this is where the significant breach is. And people feel viscerally betrayed by their institutions at the moment.

I mean, the stories that we've got coming out of the Royal Commission are absolutely gob smacking.

And every single Royal Commission that's coming after that, age care is another further erosion of trust in our institutions.

And a further erosion of trust in, I guess, the way that we've treated our most vulnerable people. So, imagine you're designing for an aged care company. Wat would you do? What questions would you ask to make sure that this outcomes that you were getting for your customers who are elderly people, in some cases, incredibly disabled, what are you doing to make their lives better and make your institution trustworthy for those people? So, given that shift we've actually got a new trust paradigm.

And this is a really exciting time in history. And it's an exciting time for designers because we are, you know, with great responsibility, with great power comes great responsibility. But we do have a huge amount of power at the moment because we're responsible for how these things are going to work and how things are going to progress into the future. And whereas there's a lot of momentum in the world and a lot of rumbling around trust.

And one of them is definitely because there's been so much of this loss of trust in those facilitating institutions like banks. Like, the government, like religion.

I mean, I don't even need to tell you the stories. I'm sure that you know when I refer to those three things where the stories are. And there's also a lot more sceptical people. So, researchers have determined that our younger generation are super sceptical and ask quite a lot of poky questions about things. And are more inclined to distrust than trust. And thirdly, we've actually got a moment in time when new technologies and new investment is coming along that can actually foster trust.

Block chain is a great example of this.

It's a fantastic example of a way to distribute trust because everything that, like, block chain allows people to embed into it the information that is true, the source of truth and throughout the distributed network it's all updated all at once.

Iceland's government is actually using block chain as its distributed network, it's distributed ledger in order to deliver government services that you can trust. There's a great project called: Providence.org and that is about salmon fishermen in Indonesia, I think. And they're using block chain to determine that this fish that was caught there in Indonesia that has a block chain tag associated with it is the fish that ends up where they said it was gonna end up.

So, that's a really interesting example.

And there's lots of opportunities for block chain in terms of trust especially in counterfitting, food counterfitting. I think there's I can't remember the stat but a massive amount of Australian beef that ends up in China actually isn't Australian beef. And wine counterfitting as well.

That's another one.

So, there's really great opportunities for these new technologies to be used for trust and increasing trust.

'Cause there are three different ways that trust manifests. There's the centralised trust.

That's the one we're really used to.

That's the banks.

These are the people, they're our institutions. And they're in a gate keeping position I suppose. They decide the rules and what exchanges go through them and how those rules work.

And we have to abide by those rules because they're the giant organisation that says so. The new ecosystems that are coming through, the platform facilitated trust.

So, these are the ones that are like Airbnb or Amazon, places where there's ratings.

So, there's a consensus of the community as to whether or not another party is trustworthy. So, this is a new paradigm that's coming though in this new digital era.

This is much more decentralised.

But it still has the gatekeepers.

And it still has the institution.

So, Airbnb effectively is the gate keeper and the institution.

But the community provides the sense of trust. And the third one is that distributed network. So, that is the block chain, the digital ledger technologies.

Once it's recorded in the ledger it cannot be removed. It's transparent so you can see when an exchange of goods or information or agreement or money actually occurred.

So, transparency's actually quite important in trust. And a sort of public network.

It's distributed.

So, any individual can have a node on this network and know whether or not something is to be trusted or not to be trusted.

So, we're moving much more towards these platform facilitated and distributed models in trust.

So, in your design practise think about what that means for you.

If you're moving away from, if you're designing for a bank and your trust is basically they go: Oh, our brand is super trusted.

Really? Is that actually gonna be future proof? Are you going to need to consider these other models of trust for that organisation? Because so much of the centralised trust has been eroded. I've got a couple of project examples.

I think I'm all right.

But I might go through them pretty quickly because. I'm all right, I'm good? Okay.

So, I wanted to give you an example of some work that we did this is a platform based trust.

So, this is a project we did for a giant telco. And they wanted to create an environment for their developers to actually grow and learn from each other. And there's a bunch of other useful workplace things that this particular platform does.

But the thing that it does to engender trust is it actually uses and I hate this word, I hate all of it: Gamification.

Okay, gamification is actually quite cool for designing for trust.

So, awarding somebody for doing something the community values.

Awarding things, getting to levels to show that you have achieved or have a certain level of mastery.

Looking at: Where do your capabilities lie? What is your capability territory? And this is a sharing platform where developers could share code backwards and forwards. They could help each other.

They could ask for ideas.

And it's an easy way for them to traverse each other's experience and use it. But the platform and the gamification, the nature of gamification in the platform created something where people could trust whether or not somebody was any good at something. And people could vouch for people's quality of code that they gave to them.

So, this is an example of some work that we did around that sort of platform based trust.

But we're still working the individual trust space as well. We did a project with Roskilde Municipality and an age care home.

And what we did was we found a lot of people who were in the aged care facility who nobody visited them ever.

And the loneliness was absolutely huge for those people. And so this project was about finding members of the community who had time an interest to go and interact with people in the age care home and actually created a buddy system.

So, we used that sort of one to one to create trust within this particular construct. And made sure that the outcome that we got was a valuable exchange for the person in the community who was coming in there 'cause they met a new person and learned things that were new.

And a lack of loneliness for the people who were in this home.

But that's that very individual trust.

So, looking at that in this particular context was a really interesting piece of work to do. There's quite a few misconceptions about trust. So, in unpacking it we found that if you keep these in mind this will help you with the design practise. So, my talk is called: Designing for Trust. Which is, like, super catchy.

But I don't think that's what you can do.

You can't say to somebody: I'm, you trust me, you trust me. You can't tell somebody to trust you.

They can only come to that realisation themselves. And say: Oh, I trust you.

So, what you're actually designing for is trustworthiness. So, you actually need to be worthy of the trust that people are putting in.

You can't fully control your brand.

You can't fully control trust.

So, if you remember, as soon as anybody starts a hashtag promotion on Twitter it always goes horribly wrong.

Vic Taxis anyone remember that one? Vic Taxis, tweet us about your fabulous experience you've had in the Vic Taxis.

And there's, like, one, that time that I was sexually assaulted by my taxi driver, LOL, Vic Taxis.

So, you can't control it.

You can't control other people's perception of your brand or other people's trust in your organisation or in your design.

The best that you can do is design for trustworthiness. And just because you can do it doesn't mean that you trust it.

Just because somebody engages with your entity doesn't mean they trust you.

Who trusts Facebook here? Who's got a Facebook account? What are we doing? Just because you do it doesn't mean you trust it. You might be using it because you don't have any other option.

I'm on Facebook because our soccer team is on Facebook, my soccer league is on Facebook.

And the only way I know what's going on is if I go on their Facebook group pages.

You're in the same position? Yeah, exactly.

I don't wanna be on Facebook.

I'm not interested in any of that stuff.

I just need to communicate with these people and that's the platform they've chosen.

So, I don't have an option.

I could make it really difficult for myself. But I've got enough difficulties.

So, I choose not.

Or you just, you might have some other priorities. Or you might just assume the risk.

So, I guess I don't really have an option in my instance. I have other priorities than making my life more difficult in itself to interact with my soccer team.

And I'm just assuming the risk.

I know Mark Zuckerberg knows a whole lot about me. But I'm just hoping that the data is big enough that I can hide or that I can be anonymized by the bigness of the data.

And trust does not necessarily equal transparency. So, I have talked a bit about transparency because the more you know about something the more you are likely to trust it.

But trust doesn't necessarily equal transparency. Trust is, it's a leap into the unknown.

And so, when you trust somebody you probably don't need too much transparency. The more transparency you demand the less you trust them. So, you know, I trust Elle, I don't require her to be transparent about pretty much anything 'cause generally she is anyway (laughs).

But the more you require that transparency the less you trust something.

And it's really common to hear these used interchangeably 'cause transparency doesn't necessarily mean clarity. 'Cause as I was saying before, how 'bout you transparently tell me how your algorithm works.

I'm probably not gonna understand it.

So, your transparency is not creating any more clarity for me.

So, really does it actually make me trust you more if you just give me a whole lot of information that I don't understand? They're striving for similar things, the trust and clarity. But the transparency and clarity.

But you're not necessarily just gonna get somebody to trust you because you tell them all of the things.

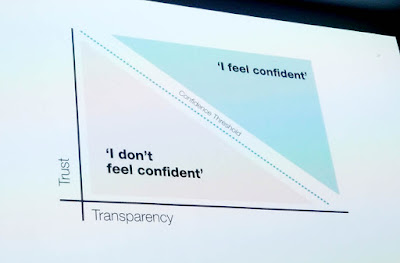

And the relationship between trust and transparency it comes as a, it's a confidence.

There are two different dimensions that we balance in order to get to a feeling of confidence. So, when you're making design decisions to design for that trustworthiness you have to decide how much clarity or how much transparency should I provide into this to get that level of trustworthiness? But also: Is it actually going to help? And everything is changing so fast.

Is my transparency about this and then it's changed in five months later? Do I just redo that again? How do we maintain transparency when things are changing all of the time? And this line here, the confidence threshold is completely subjective.

And it changes from one person to the next how much trust you have versus how much transparency there is.

This is different for every single human being. I know I'm probably not making it much easier for you to like design for trustworthiness but at least what I'm hoping to give you is a bunch a stuff to think about and questions to ask yourselves and to ask your teams and to ask the people that you're working with. What we're trying to do is we're trying to understand the people who we're designing for and we're trying to set up conditions for them to feel like they're in their confident zone by enabling transparency and building trustworthiness. And the only way that you can do that is through human centred design.

And understanding the people that you're trying to design for.

And where their confidence threshold is 'cause it's different for everyone.

I would include some stuff around this in your interview scripts going forward.

And trust is not absolute.

We definitely talk about trust in an absolute sense. We say: I trust you, I don't trust you.

I'll never trust you again.

It's like, it's a super absolute way that we talk about it. And quite frequently conversations that we have about trust we probably stay at that level.

They would tell you whether you do or don't trust something. But if you dig down into the comments that people make about this you'd actually find out the detail about why they do or don't trust, which is as we know as design practitioners we know that that's super important, the why of it. Whether they trust or not is kind of neither here nor there. The why of it is much, much more interesting and much more informative as to how we can design things going forward. Trust is really subtle.

It's dynamic, it changes.

Your sense of whether you trust or don't trust something can change and it can break very, very easily. And cultural constructs, biases, fears, all of that comes into what we do or don't trust. So, for somebody from one particular cultural background and form another cultural background where their confidence line is and what they do or don't trust are very, very different. Everybody's made up differently.

I know, I'm making it even worse, aren't I? It's very nuanced (laughs).

And trust actually if you break it down into that detail there's ways that you can unpack it.

So, trust can be made up of ability, which is the skill that an entity has at its disposal to get something done.

So, are they actually able to get the job done? The first thing that people often try to figure out before they're gonna trust something is: Is this human or entity competent? Can it do the thing that it's saying that it's going to do? We also unpack trust into benevolence.

Does this entity's intention towards the people that they're serving, is it well-meaning? Do we have aligned values? Are they in it just for themselves.

So, those are things that you ask in terms of whether or not you trust something around the benevolence.

And the third thing is around integrity.

So, is this entity, is this institution, is this human are they being honest? Are they upholding their promises to me? Are they telling the whole truth? Is there an actual, real intention to deceive me? So, trust breaks up into a whole bunch of nuanced and interesting areas.

And puling together, say, an interview script or something like that to determine whether or not or why somebody would trust. If you pull from these different facets it will give you those sort of detailed answers that you're probably asking for.

And you can build trust in a lot of ways.

Point one is, it's gonna take time.

It does not happen straightaway.

You cannot just go (snaps) boom, I'm super trustworthy. It's also gonna be continually in question. Once somebody trusts you once it doesn't mean they're always gonna trust you. And you have to keep on checking in.

Is this trust still in place? And if you break it it is incredibly difficult to get it back.

But interestingly trust can be reinforced at the moment where it's broken. So sometimes with the people we design for if they get into trouble us helping them get out of trouble regardless of whether it was the fault of the design or whatever we'll actually make them come back and trust us more. Somebody who goes through a hard time with somebody. Think about your own personal lives.

When you go through a hard time with somebody and then you come out of it the other side your trust in that human is actually reinforced. It's stronger.

Okay, I'm gonna keep going because I'm gonna run out of time.

Some design techniques in designing for trustworthiness, so, designing for trust is the idea of trust displacement. Now, I got three ideas that you can use for this. And that's just stopped bloody working.

Right.

The concept of a trust partner.

So, this is where you bring in a partner organisation or a partner human whom you can leverage their reputation. So, if you were, say, some sort of car seat manufacturer for babies what you could do is you could take Volvo as your trust partner and go: We're in partnership with Volvo and, they're super safe.

Everybody knows their reputation for safety. And because we're in partnership with them you can trust us.

So, this is the idea of trust displacement to a partner. So, this is something that you could use in your design. Provided you are not deceiving people.

There's also trust displacement through authority. So, this is where you can introduce a figure of authority. And it doesn't always need to be a top-down, reinforcing legislation authority.

It could be particular subject matter expertise or a set of values.

For example, a good example of a set of values is B corps. So, if you become a B corp you align to their set of values. And because that is stamped on your company people who also subscribe to those values will know that they can trust you.

And transparency it doesn't necessarily mean trust as I said before.

But it can be a trigger for trust.

And not just because it helps build up the track record. It actually manifests in intention that we can relate to the benevolence and integrity. So, as soon as the transparency's in high demand as I said, there are low levels of trust.

But over time if the transparency is used to build trustworthiness then it should become less relevant for people. So, I wanna end on this thought, which is, we have a huge responsibility as design practitioners. Manipulation is not our purpose in designing for trustworthiness.

Please don't go and take this and use it for evil. It's not too hard to imagine that you could pair this up with some behaviour design and off you go to.

Who am I gonna rag on? Betting companies, to some sort of betting company. Sorry if you're from a betting company.

I'm just gonna stop there otherwise it'll turn into a massive, massive rant. But you could take it and it could become a malicious plan to deceive people if you use this for evil.

And this is kind of what we call: A trust washing scenario. So, you sort of wash over the shitty thing with something that looks trustworthy.

And create a deception for the people who are using it. And it's part of our responsibility to make sure that we drive this in the direction where we're actually looking for good societal benefit and outcomes and creating trust in the right things.

So, my final thought to you is, with everything that I've given you today, do not trust wash.

Really, really important takeaway.

This is not to be used for evil.

Because we really wanna take on the human perspective when we're shaping the futures.

And it's an incredibly interesting inflexion point that we're at at the moment.

And if you're working on machine learning projects or AI this is even more important because you are functioning in the land of invisibility. And what matters tomorrow is designed by us here today. So, the runway is incredibly short.

If you have not started your engines on this one yet you've got some very quick work that you need to do to be up and ready for the challenges that are coming from you.

Thank you so much.

I would also like to acknowledge Sophie and Guille two of my designers who put in a huge amount of research work into this presentation.

And thank you all for your very kind attention. (group clapping) (vibrant electronic music)